Palmyra Cove is a 250-acre urban oasis along a highly developed area on the Delaware River. Habitats include wetlands, woodlands, meadows, wild creek and river shoreline, and a freshwater Tidal Cove after which the cove is named.

The Institute for Earth Observations at Palmyra Cove is a STEM educational initiative for students and teachers that studies Planet Earth. This is a unique and engaging facility where experiences can be shared…and innovative collaboration begins!

THE LEARNING TRAIL

DREDGE CELL

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) utilizes Palmyra Cove Nature Park as a dredged material placement facility to manage sediment from the Delaware River. The process begins with sediment being pumped into barges, which transport it to Palmyra Cove. Once there, the sediment is stored, water and sediment are separated. The cleaner water is then returned to the river, reducing sediment buildup. The most recent project involved dredging 425,000 cubic yards of sediment from south of the Tacony-Palmyra Bridge all the way up to and including the Fairless Hills Turning Basin. Sediment will be mechanically dredged (bucket/clamshell), placed in barges, and ultimately moved to Dredged the Material Placement Facility at Palmyra Cove. The project operates through a systematic process: dredged sediment is pumped into barges, which carry it to Palmyra Cove Dredge Cell. The sediment is then stored in the cell, where water and sediment are separated. Finally, the water is returned to the river with less sediment. This initiative plays a vital role in maintaining a 40-foot-deep channel for maritime commerce while also helping to mitigate flood damage from coastal storms.

DELAWARE RIVER

A watershed is an area of land where all water will run downhill and collect in a main body of water. In this area around Palmyra Cove, all the smaller streams flow down and end up in the Delaware River, hence why this is called the Lower Delaware River Watershed. Because the Delaware River is not dammed from the ocean, it also has high and low tides (or “is tidal”) all the way up to Trenton. The difference in tides is more significant up river than in the bay, up to 10 feet.

TREES & PHOTOSYNTHESIS

Photosynthesis is the process by which trees, plants, algae, and some bacteria convert sunlight into energy. Trees absorb carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the air and water (H₂O) from the soil, using sunlight to produce glucose (C₆H₁₂O₆) for growth and releasing oxygen (O₂) as a byproduct. This process is essential for life on Earth, as it forms the foundation of the food chain and provides the oxygen that humans and animals breathe. Trees play a key role in Earth’s natural cycles, acting as nature’s filters and stabilizers. In the carbon cycle, trees absorb CO₂, reducing greenhouse gases and storing carbon in their trunks, roots, and leaves. In the oxygen cycle, forests serve as the planet’s “lungs,” producing the oxygen necessary for human and animal survival. The water cycle also depends on trees, as they draw water from the soil and release it into the atmosphere through transpiration, influencing rainfall patterns and maintaining climate stability. Additionally, trees contribute to the nutrient cycle by shedding leaves and organic matter, enriching the soil for future plant growth.

WATER and the WATER CYCLE

Water is a remarkable substance with unique chemical properties that make life on Earth possible. Its polarity allows it to dissolve many substances, earning it the title of the “universal solvent.” Water’s high specific heat helps regulate temperatures, preventing extreme climate fluctuations. Its cohesion and adhesion enable capillary action, allowing water to move through soil and plants, sustaining ecosystems. Additionally, water is one of the few substances that expands when frozen, making ice less dense than liquid water— allowing it to float and insulate aquatic life in cold environments. The water cycle ensures that this essential resource is continuously purified and distributed. Through evaporation, water rises into the atmosphere, condenses into clouds, and returns as precipitation, replenishing lakes, rivers, and groundwater. This cycle supports all living organisms, maintains weather patterns, and sustains agriculture. Without the water cycle, Earth’s climate would become unstable, and ecosystems would collapse, making water not just a chemical necessity but the foundation of life itself.

WHITE TAILED DEER

Deer eat leaves, grass, and other plants, which contain cellulose that’s tough to digest. To break it down, deer have a special four-part stomach. First, the rumen stores the food, which the deer swallows quickly and then chews again, called “chewing cud.” In the reticulum, microorganisms live and break down the cellulose into usable nutrients. After chewing the cud again, the food moves to the omasum, where water is absorbed, and then to the abomasum where special juices help further digestion. Finally, nutrients are absorbed in the intestines, and waste is passed out. This process involves a symbiotic relationship between the deer and microorganisms, helping each other for mutual benefit. White-tailed deer are the most common type of deer in North America. They change colors with the seasons, becoming grayish in winter and tannish to reddish brown in summer. Their large tails are white underneath, and when they feel threatened, they raise them like a flag. Bucks, or male deer, grow antlers that don’t branch out after their first winter.

PEREGRINE FALCONS

The largest Falcon found in New Jersey, Peregrines are the fighter jets of the raptor world. They specialize in hunting birds like Pidgeon and/or waterfowl, using precise acrobatics at incredibly high speeds to catch their prey in mid-air. With exceptional vision, a peregrine can spot medium sized prey from at least 1 mile away. That’s like a human being able to spot a rabbit at a distance of over 17 football fields away! Once spotted, the falcon sets up its attack dive. This dive, called a stoop, sees the peregrine tuck in it’s wings and reach speeds of over 200mph. The fastest ever clocked hit about 245mph! During this dive the Peregrine’s incredible eyes are processing images at almost 3 times the rate that human eyes can, giving them the ability to precisely track their moving target. Historically nesting on cliffsides and other ledges high up, structures like bridges and skyscrapers are their new more common nesting locations. Our nest box on top of the Tacony-Palmyra Bridge is a perfect example of these nesting preferences. Look up and you might just see the Peregrines flying to and from their nest!

FUNGI

There are many types of fungi that live in the woods, on trees, and in the soil. Fungi are special organisms that are not plants, animals, or bacteria. They can look like mushrooms, molds, or yeast. Fungi are important because they help break down dead plants and animals, which return nutrients to the soil. Fungi don’t make their food from sunlight like plants do. Instead, they absorb nutrients from things around them, like fallen leaves, dead trees, and even animals. They are like nature’s recyclers, helping to clean up and make sure the ecosystem stays healthy. At Palmyra Cove, you can find fungi in places that are moist and shady, like near streams, in the woods, or after it rains. Some fungi are easy to spot, while others are hidden in the soil or on tree trunks. Fungi are also important because some are used in food, like the mushrooms you might eat on a pizza, or in medicine, like penicillin, which helps fight infections. So even though fungi might seem strange, they play a big role in keeping nature and humans healthy!

MUSSELS

There are at least 7 species of freshwater mussels found at The Cove, one of the last sanctuaries for these incredibly important invertebrates. Closely Related to clams, Freshwater Mussels are filter feeding bivalves that trap pieces of sediment and microorganisms in mucous as they pump water through their gills. Some of these mussels can filter over 16 gallons of water every 24 hours and are one of the biggest reasons for the ongoing improvement in water quality in this section of the Delaware River. Look for the shells of these threatened invertebrates on the beach at low tide!

LICHEN

Lichen, unlike fungi that grow beneath bark, typically grows on top. While most lichen is edible, some, like Wolf Lichen, are poisonous. Lichen has various uses, including in dyes, clothing, perfumes, toothpaste, ointments, and even medicines due to its antibiotic properties. In Japan, it’s used in paints for its antimildew qualities. Ancient Egyptians and Arab plainsmen have used dried lichen to make bread. Lichen also serves as food for animals and nesting material for birds, while protecting trees from harsh weather. With over 3,600 species in North America alone, it grows on surfaces like rocks, trees, and even buildings. Lichen is a keystone species, vital to ecosystems, as it absorbs pollutants like sulfur, mercury, and nitrogen, helping to improve air quality. It is sensitive to air pollution, and studying its species can provide insights into environmental health

WILDFLOWERS

Wildflowers are flowers that grow naturally without people planting them. At Palmyra Cove, you’ll find colorful flowers like purple violets, bright yellow sunflowers, and bluebells. These flowers are important because they provide food for bees, butterflies, and other animals. Some flowers even help clean the air and soil! When you walk through the cove, you might also spot different birds and insects visiting the flowers. It’s a great place to explore nature, learn about the environment, and enjoy the beauty of wildflowers.

INSECTS

There are many cool insects to discover, other than butterflies and caterpillars! One insect you might spot is the dobsonfly. It has huge, jaw-like pincers, but don’t worry, it’s not dangerous. Dobsonflies live near water, where their larvae grow in streams before they turn into adults. Another interesting insect is the firefly, which lights up at night. These glowing insects use special light to talk to each other, creating a beautiful show in the dark. You might also see dragonflies and damselflies near the water. These insects are great at flying and catching smaller insects to eat. Ants are very busy at Palmyra Cove, working together to find food and protect their nests. Some of these ants, like red fire ants and the red velvet ants, can sting, so it’s best to watch from a distance! The ground beetle is another insect you may find hiding under rocks or logs. It helps by eating pests that can harm plants. These insects, though small, play important roles in nature by pollinating plants, eating pests, and helping the environment stay balanced!

BUTTERFLY MEADOW

Butterflies are everywhere, especially in the spring and summer! Butterflies love the colorful wildflowers that grow there, like milkweed and goldenrod. These flowers provide nectar, which butterflies drink to stay healthy. You might see different kinds of butterflies at Palmyra Cove, such as the orange and black Monarch butterfly or the bright yellow Tiger Swallowtail. Butterflies are important because they help pollinate flowers, which means they help plants grow and make seeds. If you’re quiet and patient, you might even see a butterfly land on a flower! Palmyra Cove is a perfect place to watch these amazing creatures up close.

BULLFROG POND

Despite its small size, Bullfrog Pond is a safe haven for all different kinds of wildlife — Birds, Mammals, and especially reptiles and amphibians. If you approach quietly – Frogs and Turtles have exceptional hearing – frogs can be found along the pond’s banks and turtles can be seen basking on logs. Unlike Humans and other Mammals that produce their own body heat, these cold-blooded organisms rely on the sun’s energy to warm them up each day. If you’re visiting during the spring, keep an eye out for another hopping amphibian! Fowler’s Toads gather at Bullfrog Pond to breed before hopping away to their usual forest homes.

BEAVER POND

Named for a family of beavers that have since moved their lodge into the tidal cove, Beaver Pond is rich with wildlife of all kinds. Aerial predators like Tree Swallows and Dragonflies can be seen darting through the air catching insects of all sizes. Herons and Kingfishers wait for the unsuspecting fish to swim near the surface and plunge into the water to secure a meal. Mink can even be seen perched on a stump waiting for their next meal to swim by. On the surface, ducks and other waterfowl gather for the food and safety the pond provides. It is for this reason that Beavers are still occasionally sighted here, so keep your eye out as you explore!

EARTH OBSERVING SATELLITES

In the Space to Earth: Earth to Space (SEES) Model, Earth Observing Satellites pass over the Living Laboratory daily, providing a unique opportunity for students to validate and refine satellite data through Ground Truth Verification. By comparing real-time satellite data with on-the-ground observations, students ensure data accuracy while enhancing their understanding of how space-based technology supports local environmental monitoring. This process connects students with both space science and real-world applications, equipping them with valuable skills for the future.

OZONE GARDEN

Did you know that ground-level ozone is a serious pollution problem? Ground-level (“bad”) ozone is toxic to plants and animals – including humans. It is different from the ozone layer (“good” ozone) high in the atmosphere that blocks the Sun’s harmful ultraviolet (UV) rays, even though it is the same chemical in both places. Ground-level ozone is harmful to us because it is in the air we breathe. Although ozone is invisible, its effects can be observed on the leaves of certain plants. Ozone sensitive plants develop symptoms on their leaves that we can see, telling us when high levels of ozone are present in the air around us. Because they provide this information, they are called bioindicator plants. However, there are still lots of questions when it comes to ozone and plants: What ozone concentrations cause damage to plant leaves? How severe does the damage get? Is it the same everywhere? Scientists are trying to understand the answers to these questions.

WILDLIFE

There are a rich tapestry of wildlife, making here a vibrant and fascinating destination for nature lovers. Among the animals that roam the area are minks, red foxes, and playful river otters. Minks are agile, solitary hunters often spotted near water, using their sharp claws to catch fish and small mammals. Red foxes, with their bushy tails and keen senses, thrive in the woodlands, adapting to a variety of diets including small mammals, fruits, and insects. River otters, social and playful, are expert swimmers and dive deep in the cove’s waters to hunt for fish and crustaceans. The cove is also home to larger mammals like white-tailed deer, often seen grazing quietly at dawn or dusk. Wild turkeys roam the forests, their distinct calls echoing through the trees, while raccoons forage at night. Snakes, such as the Eastern garter snake, slither through the underbrush, playing an important role in controlling insect and rodent populations. Bird watchers can spot a variety of species, from herons and egrets to red-tailed hawks soaring high in the sky. The wetlands also attract ducks and geese, making the area a key stop for migratory birds. This mix of forest, wetland, and river habitats creates a rich environment where a wide range of animals—big and small—thrive, making Palmyra Nature Cove a haven for wildlife and an exceptional place to explore nature.

WILD TURKEYS

Wild turkeys are a common and fascinating sight. These large, native birds thrive in the park’s diverse habitats, often spotted near the Interpretive Center and along the park’s scenic nature trails. Wild turkeys are known for their striking appearance, with males displaying iridescent feathers and distinctive wattles on their necks. Fun fact: despite their large size, wild turkeys are excellent fliers and can reach speeds of up to 55 miles per hour in short bursts. They’re also skilled runners, capable of sprinting up to 20 miles per hour. Wild turkeys are omnivores, feasting on a wide range of food, including seeds, nuts, insects, and small reptiles. Palmyra Cove offers a perfect setting for birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts to observe these majestic creatures in their natural environment.

TACONY PALMYRA BRIDGE

The Tacony-Palmyra Bridge, designed by renowned engineer Ralph Modjeski—who also worked on the Manhattan and Benjamin Franklin bridges—was built to replace a ferry service between Palmyra and Tacony that started in 1922. Construction began in February 1928, with the bridge opening to traffic on August 14, 1929. The bridge features a variety of structural elements, including a through-tied arch over the river, a double-leaf bascule span for marine traffic, and several truss and girder spans. The bascule span operates like a seesaw, with a counterbalanced rising floor powered by two rolling lifts. The total construction cost was about $4 million, and the bridge was acquired by the Burlington County Bridge Commission in 1948. Notably, no tax money from Burlington County residents is used for its maintenance. The bridge is 3,659 feet long, 38 feet wide, and supports three lanes of traffic (two towards Philadelphia and one towards New Jersey), as well as pedestrian access. In 1977, the lanes were narrowed from four to three. The bridge has a 61-foot vertical clearance under the main arch span at high tide, with a minimum of 54 feet under the bascule span. Marine vessels requiring more clearance must request a bridge opening, temporarily halting vehicular traffic until the passage is complete. As of this date in March of 2025 the cost to drive over the bridge into PA is $4.00 cash or $3.00 EZ Pass. INFO from WEBSITE Design/Building • Designed by Ralph Modjeski (engineer of the Manhattan Bridge and the Benjamin Franklin Bridge) • Bridge replaced the existing ferry service, which began operating between Palmyra and Tacony in 1922 • Built by the Tacony-Palmyra Bridge Company after receiving approval from both the United States Congress and the United States War Department Construction began in February 1928 • Bridge opened to traffic August 14, 1929 • Comprised of several different types of structures: – A through-tied arch at the middle of the river – A double-leaf bascule span – Three-span continuous half through-truss spans – Deck girder approach viaduct spans January 1929: Erection of bascule span, which operates like a balance or seesaw—the rising floor section is counterbalanced by a weight; two rolling lifts power the bascule span Cost • In 1928-1929, total cost was approximately $4 million • Acquired by Burlington County Bridge Commission in 1948 • No tax money from Burlington County residents is used to maintain this bridge Specifications • Total length from abutment to abutment is 3,659 feet • Bridge is 38 feet wide and carries three lanes of vehicular traffic (two into Philadelphia and one into New Jersey) and also pedestrians across the river. • In 1977, lanes were widened, thus changing from four lanes of vehicular traffic to three Clearance/Openings • Vertical clearance under main arch span at the center is 61 feet at high tide • Minimum vertical clearance under bascule span at high tide is approximately 54 feet • Marine vessels requiring a vertical clearance greater than that of the movable span in its normally closed position must request a bridge opening. • The bascule span leaves are raised to permit passage of the vessel and vehicular traffic on the bridge is temporarily stopped until the vessel clears the bridge; the span then resumes its normal lowered position.

WATERFOWL

At Palmyra Cove Nature Park in New Jersey, bird enthusiasts have observed a diverse array of duck species. Notably, sightings include the Long-tailed Duck (Clangula hyemalis), with two individuals confirmed on March 12, 2025. Additionally, the Redhead (Aythya americana) has been spotted, with three observed on March 9, 2025. Other commonly reported ducks in the area encompass:

- Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos): Males are distinguished by their iridescent green heads, while females display mottled brown plumage.

- American Black Duck (Anas rubripes): These ducks exhibit dark brown feathers with subtle iridescent purple speculum feathers.

- Green-winged Teal (Anas crecca): The smallest North American dabbling duck, males showcase a distinctive green head with a chestnut-colored body.

- Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola): A small diving duck, males possess a striking black and white body with an iridescent green and purple head.

- Common Merganser (Mergus merganser): A large diving duck, males feature a distinctive black head with a white body, while females are brown with a grayish body.

These observations underscore the park’s significance as a vital habitat for various duck species, making it an excellent destination for birdwatching enthusiasts.

HERONS

Birdwatchers can spot several species of herons, each with its own unique traits. The Great Blue Heron, the largest in North America, is easily recognizable by its tall stature and striking blue-gray feathers, often seen wading in shallow waters to hunt for fish. The smaller Green Heron, with its rich greenish plumage, is more secretive and tends to hunt from the shadows, waiting for prey with incredible patience. Another species, the Black-crowned Night Heron, is known for its nocturnal habits, with a distinctive black cap and white body, often seen hunting in low-light conditions. Lastly, the little Snowy Egret, while not technically a heron, can be found in the cove, known for its pure white feathers and elegant, slender build. These herons bring a diverse range of behaviors and appearances to the natural beauty of Palmyra Nature Cove, making it a prime location for birdwatching.

EAGLES

Eagle enthusiasts can witness one of nature’s most magnificent birds here—the bald eagle. Located along the Delaware River, this wildlife sanctuary provides a critical habitat for these majestic raptors. During the winter months, the area becomes a prime location for spotting bald eagles, which migrate to this region from northern parts of the United States and Canada in search of open water and abundant food sources like fish. The Cove’s diverse ecosystem offers the perfect environment for these apex predators. Eagles can be seen soaring above the river or perched on tall trees, scouting for fish in the waters below. The park has become a crucial part of the Eagles Nesting and Migration Program in New Jersey, helping protect eagle populations and giving visitors an opportunity to see these birds up close. Bald eagles are renowned for their keen eyesight, which allows them to see up to 3-4 miles away—about eight times sharper than a human’s vision. This exceptional vision helps them spot prey from great distances while soaring high above the landscape. Additionally, bald eagles are known for their strong pair bonds and unique mating habits. They typically mate for life, often returning to the same nesting site year after year. The courtship process involves elaborate aerial displays, with the male performing acrobatic flights to impress the female. These powerful birds have a wingspan of up to 7.5 feet, which helps them glide effortlessly across the sky. The park’s efforts to conserve their habitats make it an important location for environmental education and birdwatching. Whether you’re a seasoned bird watcher or a casual visitor, a trip to Palmyra Cove offers a unique chance to connect with these awe-inspiring creatures.

NESTING BOXES

The bluebird and swallow boxes provide critical nesting sites for these two iconic species. The Eastern Bluebird, with its striking blue feathers and orange chest, is a cavity-nesting bird that thrives in open fields and meadows. Bluebird boxes are carefully placed to offer a safe place for them to build nests and raise their young, helping to boost local populations that once faced decline due to habitat loss. Tree Swallows, agile and glossy with iridescent feathers, also rely on cavity nests. These birds are expert aerialists, feeding on insects like mosquitoes and dragonflies. Swallow boxes are strategically positioned near water or wetlands, where these swallows can find abundant food and suitable nesting areas. These nesting boxes serve as vital support for both species, offering sanctuary in the park’s lush, diverse habitat. The Cove’s efforts not only help increase these bird populations but also provide the public with a chance to observe and engage in conservation firsthand.

MONARCH BUTTERFLIES

Monarch butterflies are one of the most iconic and unique species in the insect world, known for their incredible long-distance migration and striking orange and black wings. What sets monarchs apart is their migratory behavior: each year, millions of monarchs travel up to 3,000 miles from North America to central Mexico, where they overwinter in forests. This extraordinary journey is passed down genetically, with successive generations completing the full migration cycle. At Palmyra Cove, monarchs are a welcomed sight during their migration, typically in the fall when they stop to rest and feed before continuing south. The Cove’s diverse habitats, including wetlands and meadows, provide a perfect environment for the butterflies to gather nectar from native plants like milkweed, which is essential to their lifecycle. Milkweed is not only a food source for adult monarchs, but it’s also where they lay their eggs, as it is the sole food source for their caterpillars. Palmyra Cove plays a key role in monarch conservation by offering a sanctuary for these pollinators, helping to ensure their populations remain strong. The presence of monarch butterflies at the park serves as a reminder of the importance of preserving natural habitats and supporting pollinator-friendly environments.

RUNNING OF THE SHAD

The annual shad run in the Delaware River near Palmyra, NJ, is a remarkable natural event that typically occurs from late March through April. This migration involves the American shad, a fish species that travels from the Atlantic Ocean back into the river’s freshwater to spawn. The Palmyra area, with its specific water conditions and historical significance, plays a key role in this journey. As the shad swim upriver, they face various challenges like navigating dams and strong currents. In the past, the population of American shad was drastically reduced due to overfishing and poor water quality, but in recent decades, conservation efforts, including dam modifications and cleaner river conditions, have led to a resurgence in their numbers. The Delaware River, particularly in the Palmyra region, has become one of the key spawning grounds for the species. During the peak of the run, the shad congregate in the river’s deeper, slower-moving waters. They can be seen moving past the Palmyra area, often aided by fish ladders designed to help them bypass obstacles like dams. Local organizations and environmental groups actively monitor the run, offering educational programs about the shad’s life cycle, the history of the fishery, and the importance of preserving the river’s health. The event also serves as a celebration of the river’s ecological restoration. The shad run has cultural significance, as it’s tied to the history of the region—early settlers depended on the shad for food, and Native American tribes once held ceremonial events related to the shad’s migration. The timing of the run, aligned with spring, symbolizes the renewal and vitality of the river and the surrounding environment. This natural spectacle not only highlights the ongoing efforts to protect the Delaware River but also draws attention to the importance of sustaining healthy ecosystems for future generations.

DECOMPOSING LOGS

Throughout the Cove’s Riparian woodlands, logs in different states of decay line the forest floor. While they might appear dead, these rotting and decomposing logs are actually small biodiversity hotspots that contain all different types of organisms that play an extremely crucial role in a healthy ecosystem.

The first one of these groups are the Microorganisms. Bacteria, Protozoa, and Fungi colonize a fallen log almost instantly. Softening the wood and weakening its bark so other organisms can begin their role in the decomposing process.

These next organisms are small insects, their larvae, and other larger microorganisms that are barely visible to the human eye. These little decomposers tunnel and eat their way through the parts of the wood that were softened by disease and microorganism colonization.

The final creatures to arrive at the log are large shredders. Usually invertebrates with strong jaws that can cut through all of the stronger wood still remaining.

These three types of creatures work together to decompose fallen logs into the dirt that we find in all of our forests.

ATLANTIC FLYWAY

Every spring and fall, hundreds of thousands of birds visit Palmyra Cove as part of an amazing journey we call migration. This journey can come in different shapes and sizes, from short migrations within regions or continents, to intercontinental trips across the globe. Regardless of length and type, birds migrate for the same two reasons – food and safe nesting locations. There are over 650 species of birds that breed in North America and more than half are migratory! Birds that nest in the Northern Hemisphere tend to migrate northward in the spring to take advantage of the abundant food that awakening insect populations provide. In the fall, these same birds – and their offspring – will fly south to their warmer, winter homes where food will still be available to sustain them. For some species this incredible journey will be thousands of miles long and require many stops along the way to rest and refuel. The path taken by these birds is not random, and in fact can be separated into four migration superhighways across North America, known as the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific Flyways. Palmyra Cove happens to be a key stop along the Atlantic Flyway, providing a key stop for birds as they refuel before taking flight for the next leg of the journey northward. Other birds stop here for good to find a mate and begin the nesting process. Regardless of whether the cove is their last stop, the insects, berries, and other food sources here have been sustaining migratory birds for thousands of years.

OSPREY

The osprey nest box is a popular focal point for birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts. Ospreys, also known as fish hawks, are large raptors that primarily hunt for fish, which make up nearly 99% of their diet. The nest box at Palmyra Cove provides a perfect home for these incredible birds of prey, offering a safe and elevated place to build their nests. Ospreys can often be seen soaring above the park’s waterways, using their remarkable eyesight to spot fish from up to 200 feet in the air. Their eyes are specially adapted for this task, with a higher density of photoreceptor cells and a special “fovea” that allows them to see details with extraordinary clarity, even when flying at great heights. Like humans, ospreys have binocular vision and a wide peripheral field, allowing them to see to the sides more effectively. Osprey eyes have four types of color sensors compared to our three, allowing them to perceive ultraviolet light along with the light visible to humans.

One fascinating fact about ospreys is that their feet are uniquely adapted for gripping fish; they have barbed pads on the soles that help hold onto slippery prey. Ospreys are also known for their distinctive call and large, powerful wingspans, which can stretch up to 6 feet. Despite being widespread across North America, ospreys were once endangered due to DDT pesticide use, but conservation efforts like the nest boxes at Palmyra Cove have played a key role in their recovery. These majestic birds are not just a symbol of the park’s vibrant ecosystem, but also a testament to successful wildlife conservation efforts.

WETLANDS

Freshwater wetlands are those areas of land and water that support a variety of characteristic wetlands plants due to the presence of wetlands hydrology or hydric (wet) soils. Freshwater wetlands commonly include marshes, swamps, bogs and ferns. Some wetlands occur where the groundwater, emerges at the surface of the ground, usually on a slope: these commonly are known as hillside seeps or slope wetlands. The most. well-recognized wetland is where surface water, such as a pond-or lake slopes up to land, where wetlands develop; these are known as fringe wetlands. Riparian wetlands occur in the floodplain adjacent to streams and rivers. Wetland Functions and Values: Wetlands perform numerous important functions, such as removing excess nutrients from the water that flow through them. These functions in turn provide benefits to the environment and the citizens of the state. For example, the benefit derived from nutrient removal is improved or maintained water quality. This in turn is valued by society for a number of reasons such as clean drinking water, safe recreation, and secure fish and wildlife habitat.

GEOLOGICAL HISTORY

The Palmyra Cove Nature Cove is situated within New Jersey’s Inner Coastal Plain, characterized by sedimentary deposits from the Cretaceous period (approximately 145 to 66 million years ago). These formations include sandstones, siltstones, and clays, reflecting a time when the area was submerged under a shallow sea.

BEAVERS

The largest rodent in the United States, the American Beaver is a highly important part of the preserve’s ever-changing ecosystem. While it is rare to see one of these amazing creatures during the day, evidence of beaver activity can be found near all bodies of water at the Cove.

Well known for their ability to build dams and fell trees, beavers take advantage of the shelter that raising the water level provides. Within these dammed up areas a large lodge is built from mud and sticks, only accessible via an underwater entrance. Two large beaver lodges built within our tidal cove can be seen at different points along Perimeter Trail, and are truly an impressive sight.

Despite being reinforced with iron, chewing through tough hardwood takes a toll on their teeth. A Beaver’s teeth will grow constantly throughout its lifespan and they must gnaw on trees to keep their teeth from growing too long! Looking into the forest behind this sign, you will see many young cherry trees missing bark and chunks of wood. This is a clear sign of beaver activity, and can be found elsewhere through the preserve if you look close enough!

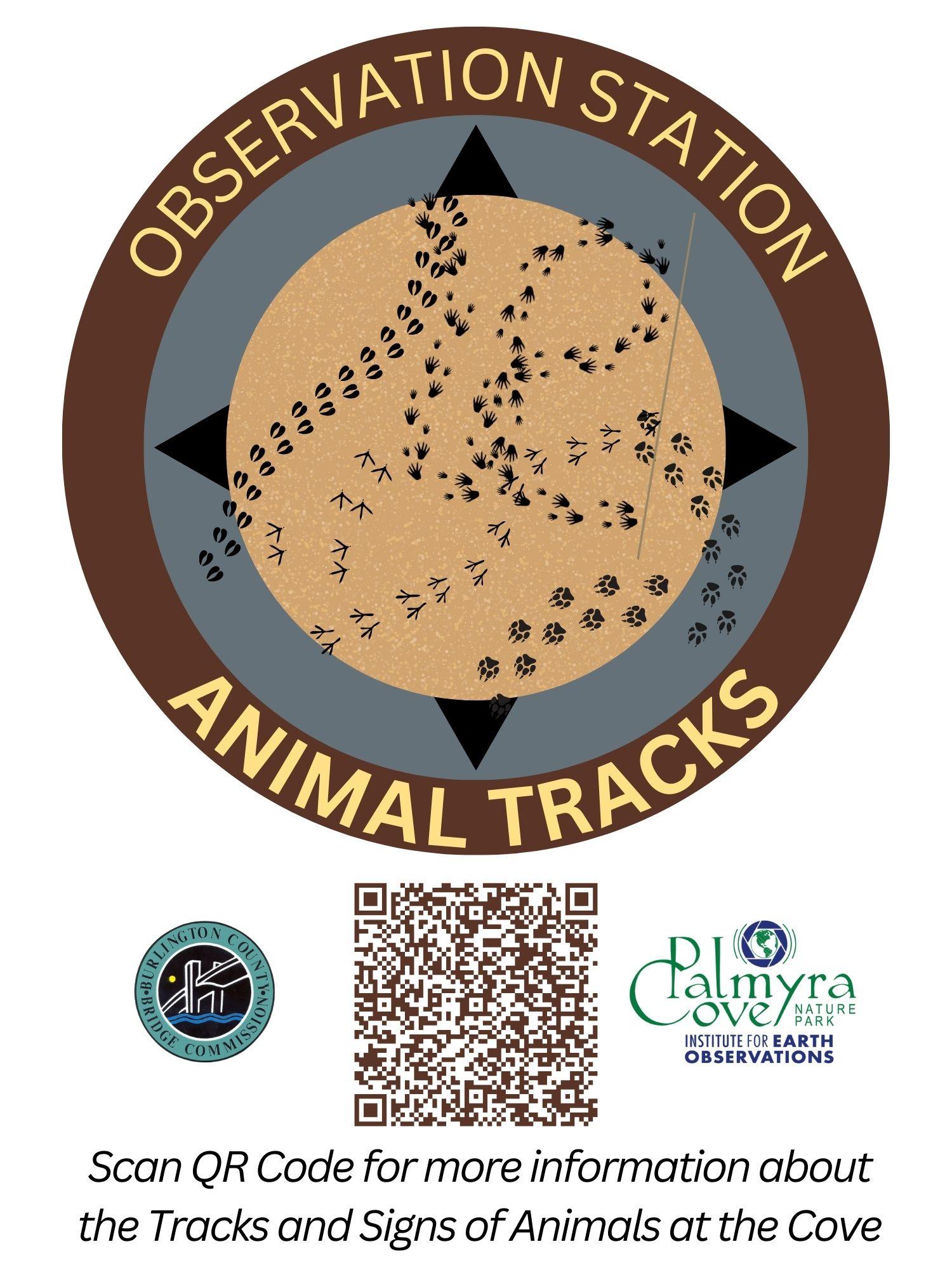

ANIMAL TRACKS

Walking through the various trails at the Cove you may notice the imprints of tracks in the loose sand and dirt. The tracks come in all shapes and sizes. Some are small like the subtle tracks of a squirrel, and others are very hard to miss, like Deer or Coyote Tracks. As you continue along the trails, use the silhouettes below to identify any tracks you may come across and/or notice! Scan the QR code for a pocket sized guide on your phone!

ROCKS & MINERALS

Palmyra Nature Cove’s geological formations primarily consist of sedimentary rocks such as sandstone and siltstone. While these rocks may not be as visually striking as igneous or metamorphic varieties, they hold valuable information about the region’s ancient environments. Mineral enthusiasts may also find iron-rich minerals and quartz deposits within these sedimentary layers.